13 June 2024

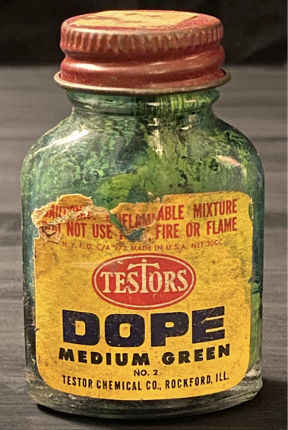

When I was a kid, I loved building planes from balsa wood kits, covering them with silk—which required the use of “dope”—attaching the little gas engines to the front and flying them control-line at the park down the street. These models only had one control surface: the elevator.

One of my friends was into this, too, which was handy. Flying a control-line model requires someone to hold the model, engine running at max, while the pilot runs out to the middle of the flight circle and grabs the control handle. The pilot yells, "Okay," the helper lets go, and the plane flies in a circle around the pilot. Stunts are limited to what you can do with the elevator. My most vivid memory is of the grass fire we started one day at the park when the motor caught fire on my friends' plane!

Much later in life, during the midst of COVID, I got back into the hobby, but this time with electric-powered, radio-control planes. Large gliders, with 2 or 2.5-meter wingspans, were my favorite. These are scale models of manned high-performance sailplanes. With these, the power is used just to get the plane to altitude. Cut power, the props fold back, then hunt for thermals just like the big birds do! Some radios are equipped with audible variometer alerts to let the pilot know if the model is gaining or losing altitude. Quite enjoyable on a warm summer day.

At some point, I learned that enthusiasts around the world were flying planes “FPV” which means first person view. Being a bit near-sighted, this sounded interesting since flying line of sight can be troublesome. Even with large models, flying at 400 feet and a quarter mile away, it can be difficult to see what’s going on up there. Take your eyes off your model, even for just a moment, and you may never find it again in the sky. Don’t ask how I know this!

You’re Flying

That must be the answer, I reasoned. Hook up a camera on the plane that transmits it’s view back to the pilot on the ground wearing a pair of FPV goggles! Search “FPV plane" on YouTube and you will find endless videos on all aspects of the subject.

Sounds easy enough, but it’s not. FPV planes share very little with the retail RC aircraft generally available. You’ve got to lean about flight controllers, video transmitters and receivers, unfamiliar brands of radio equipment, GPS receivers, and much more. After the plane is physically built, then you must program the flight controller by hooking it up to your computer and working with special software. Learning this critical piece can take just as long as learning to build FPV. Most local hobby stores are aware of FPV, but only regarding drones. They offer no help to the fixed wing FPV pilot. Everything I learned was from YouTube videos and special interest groups on Facebook.

Once you’ve finally gotten your first FPV plane into the air, it’s truly amazing. The visual experience is very similar to being right in the cockpit of the plane. You’re flying!

Not only that, but you’re also freed from the limitations of line of sight. Long distance flying is a thing. Records kept by radio equipment makers show that pilots are flying 20 miles out and more! My best is a bit over three miles out.

At some point, I stumbled upon a video about a commercial-grade plane equipped with specialized camera equipment (a.k.a. “payload”). It was being used for mapping a large land area slated for development. Not just that, the craft was being flown “autonomously” via a mission that had been planned prior to flight. This was yet another pivotal point for me. I’m thinking, “So, these things can be put to work—not just flown for hobby.”

Having made a career in information technology, I was intrigued with the idea of downloading a “mission” to an unmanned aircraft and sending it aloft to do a job. As I begin to explore this, I could see that indeed it was a marriage of hardware (aircraft) and software. The fixed-wing mapping plane turned out to be an outlier. Yes, there are a few manufacturers offering VTOL (vertical take-off and landing) planes with a variety of payload options. But it quickly became obvious that the industry standard unmanned aircraft was of the quad copter variety. Most simply refer to them as “drones.” Common definitions of the term drone do not distinguish between fixed-wing and multi-rotor. Make no mistake though, when people speak of drones, they mean quad copters.

Prior to this latest epiphany, all I knew about drones, particularly those equipped with FPV, was for racing. I had no interest in that, so I mostly ignored them. But now that I had discovered that drones were being put to work in various ways, I had to find out more.

A Mini for Me

So, I bought my first drone. A factory refurbished DJI Mini 3 Pro with a standard RC-1 controller. This is the controller that does not have a built-in display screen. That turned out to be a stroke of luck because some of the popular 3rd-party software works fine with the RC-1 controller but is not compatible with the more popular controller with the built-in screen!

I signed up for a subscription with Dronelink and bought a good android tablet to use with the DJI RC-1 controller. Interestingly, Dronelink is not compatible with iOS devices.

Soon I was planning mapping missions of various areas nearby. No doubt I held my breath the first time I sent my new drone off on a mission over a heavily wooded area along a river! With the mission complete, my drone returned to “home” and landed itself perfectly on the bright orange landing pad.

Tools, Not Toys

Once back at mission headquarters, and after reviewing the astonishingly high-quality images that had been collected, I had yet another pivotal moment. The 249-gram drone sitting on my desk was a tool, not a toy, and it had just finished its first job it had been assigned.

Now I was getting really motivated. After 39 years in corporate information technology, I was planning to retire soon. I’m the type that needs to stay busy and had been looking for something to do post-retirement. If it could be mostly outdoors, even better. Starting a drone service provider business seemed to check all the boxes.

Hang on partner, there’s that licensing thing: The Part 107 test.

Yeah, that thing. I downloaded everything free I could find, mostly from “dot gov” websites. But there didn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason to a lot of it. I quickly became frustrated, so I did a quick look around and decided to sign up with The Drone U for their virtual prep classes and downloadable study materials. Is this the best way? I don’t know but it worked for me. I spent about six weeks studying the material and practice tests a few hours each night.

I’m Screwed

The day of the test came. Arriving early at the testing center, I noticed that everyone milling around in the building were wearing airline uniforms. The testing center assist escorted me a small room of cubicles and went over the procedure. I had a computer, keyboard, mouse, and a big book full of aviation diagrams and sectionals. There was a camera on the ceiling pointed straight at me and various laminated signs hanging on my cubicle wall. “Flip this one over if you need a break. Flip this one over when you’re finished. I’ll be watching.” the assistant said.

I started the test and read the first question. Mind you I had practically memorized the extensive practice tests supplied by The Drone U. I had read every word of their 391 page “Part 107 Drone Certificate Study Guide.” Some of the material I read multiple times (airspace, weather, and regulations.) But as I sat their staring at the first question, first I’m thinking “what is this? I don’t remember this at all.” Panic started to creep in. Now I’m thinking, “if this is the way it’s going to be, I’m screwed.” Finally, I decided just to mark the question for review and move on.

That turned out to be the right decision. From there on, the questions started looking familiar. In fact, some were verbatim right out of the practice tests. By the end, I had six questions marked for review out of the sixty on the test. One-by-one I went back to each of them, first to memorize so I could write them down later, and of course to try and do my best to answer each one.

Finishing the test, I flagged the assistant. She came to get me and ask me to follow her back to her desk for scoring. I won’t lie, I was nervous. The thought of going through all this again was not pleasant.

At last, she said “Hey, pretty good score. You made a 90!” With incredible relief I told her that I was surprised at the test difficulty. I took the printed report she handed me and made my way out of the building. Yes, a 90 means six questions missed out of sixty, but they don’t tell you which six were missed.

Back at my car I tried to write down everything I could remember about the six questions that stumped me. Later, I emailed them to Mahesh at The Drone U so they could be included in future revisions of their study material.

So that brings my story to the current crossroads where I find myself: Retiring from an uninspiring 9-to-5 corporate career and starting a new venture with opportunity, and risk, all around me. Would I be better off financially if I ”hang in there” for a few more years? Unquestionably. Would I be happier, and arguably healthier, getting out sooner? No doubt. I couldn’t be more excited about what lies ahead!